A Complete Guide to Chord Symbols in Music

We’re here to give you a rundown of what these chord symbols mean and how to use them!

Chord symbols in music can be confusing, simply because there are a lot of them. These symbols consist of letters, numbers, or symbols that indicate the root (or tonic) on which the chord should be built, as well the quality (major, minor, etc.) of the chord. Most sheet music contains notated melodies with chord symbols written above them, and we’re here to give you a rundown of what these symbols mean and how to use them.

Letters

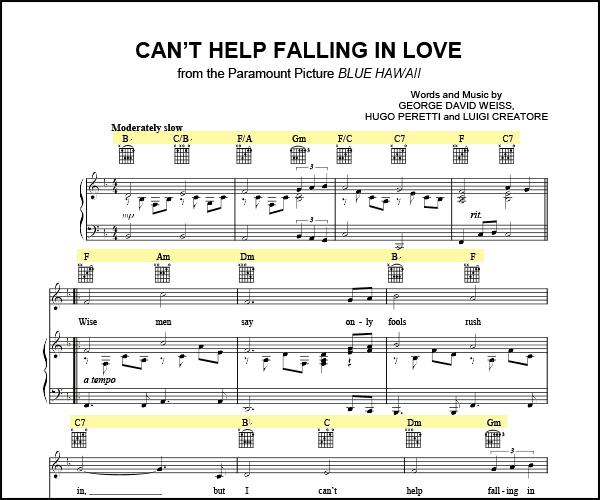

The first thing to understand in chord symbols is the letters. The uppercase letters you will see in chord symbols are C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. Each of these letters may also be accompanied by a sharp (♯) or flat (♭). These letters (with and without accidentals) represent all of the notes on the staff. Let’s look at the following song, “Can’t Help Falling in Love” by Elvis Presley.

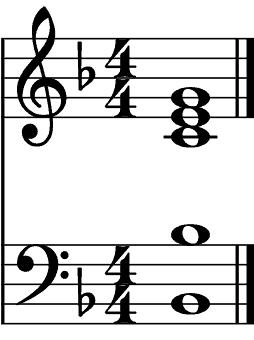

The letters you see represent the root or tonic (the first note of any major or minor scale) of the chord being built. Looking at the beginning of the piece, we see a B♭, which means that the tonic of that chord is a B♭. Moving to the next chord we see a C/B♭. Now that we have two letters to look at, things can get a little confusing. The first letter, C, is our primary chord, and therefore the tonic has switched from B♭ to C. However, C/B♭ means that a C chord is sounding over (or on top of) a B♭ (the note only–not a chord). Written out, C/B♭looks like this:

Continuing past C/B♭, F/A follows the same rule: an F chord over an A. Next we have Gm, meaning that G is the tonic of that chord. In addition to the previously mentioned letters, you may see an “M” or two on your music, which leads us into our next section: chord quality.

Chord Quality

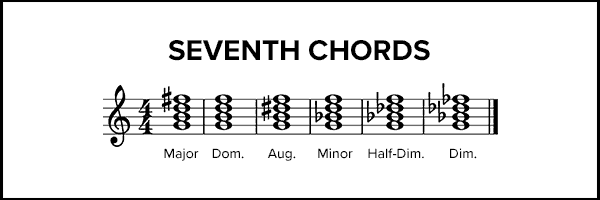

Chord quality refers to the component intervals that define the chord. The primary chord qualities are:

-

- Major and Minor

- Dominant

- Augmented, Diminished, and Half-Diminished

If you need a refresher on what these terms mean, check out our Glossary of Musical Terms or our article How to Read Sheet Music: Step by Step Instructions.

Major Chords

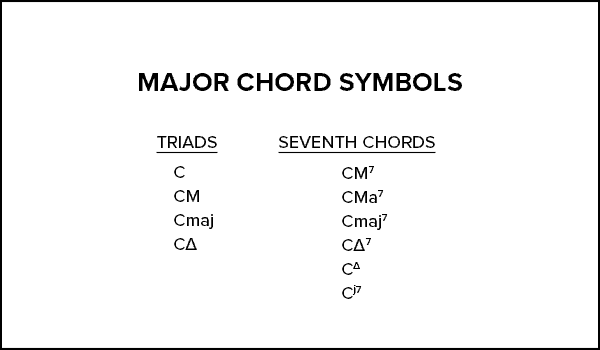

Major chords are most commonly represented by an uppercase letter with no other symbols. For example, if you see the letter “A” on a lead sheet, you can assume it’s an A Major chord. However, when it comes to seventh chords, you must place a capital “M” next to the letter, for example, AM7. Without the “M”, as we will see in the section on dominant chords, the chord will be assumed as dominant instead of major. The following symbols can all indicate major chords:

Minor Chords

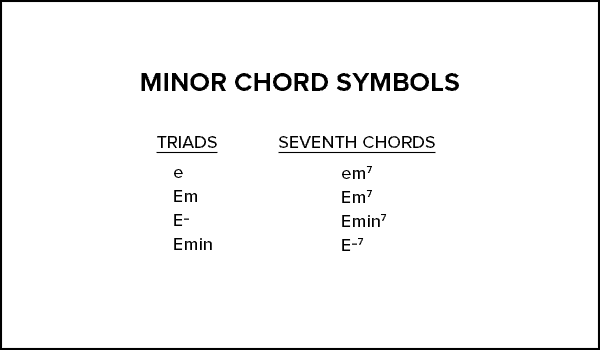

Minor chords are most commonly represented by lowercase letters, either accompanied by a lowercase “m” or by themselves, for example, d or dm. The lowercase letters can get confusing when it comes to letters like c, a, and f, so adding the “m” is usually preferred by musicians. Minor chords may also be represented by an uppercase letter and a lowercase “m,” for example, Dm.

Dominant Chords

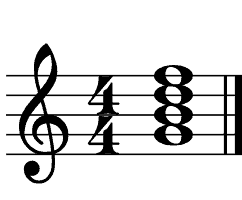

The dominant chord in a major or minor key refers to the chord built on the fifth scale degree. For example, the dominant chord in the key of D Major is A Major. However, the only time a symbol accompanies dominant chords is when they are dominant seventh chords. These are also known as major-minor seventh chords because their structure is made up of a major triad and a minor seventh. The following is an example of a G Dominant Seventh Chord in the key of C Major:

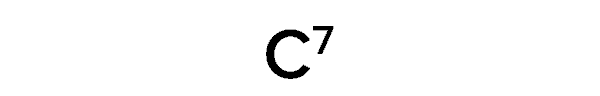

The dominant seventh chord is one of the most straightforward chords to identify because it only has one form:

It is merely an uppercase letter accompanied by a 7. The “7” may look small as it does in the example above, or regular sized, as “C7.” Either way, it signifies a dominant seventh chord.

Because the dominant chord is represented by only a letter and the number 7, you must remember to add an uppercase “M” or any other symbol you wish to use to indicate a major seventh chord. The two chords sound very different but are easily confused.

Augmented, Diminished, and Half-Diminished

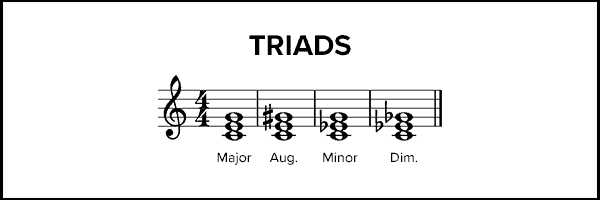

Augmented, Diminished, and Half-Diminished chords all pertain to the fifth in the chord. Augmented means to raise the fifth by a half-step while diminished means to lower the fifth by a half-step.

Regarding triads,

-

- An augmented triad consists of a major triad with a raised fifth

- A diminished triad consists of a minor triad with a lowered fifth

Regarding seventh chords,

-

- An augmented seventh chord consists of a dominant seventh chord with a raised fifth

- A diminished seventh chord consists of a seventh chord with all minor intervals

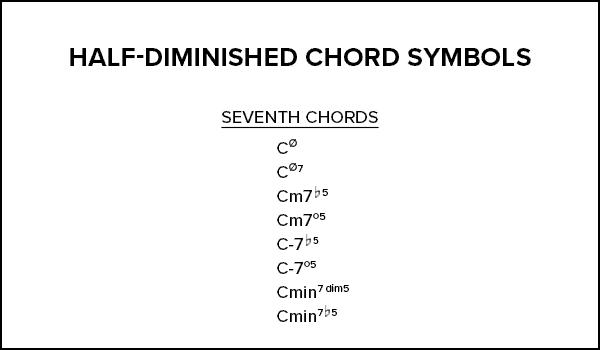

- Half-diminished chords only occur with seventh chords, and they consist of a diminished triad with a major third between the fifth and the seventh

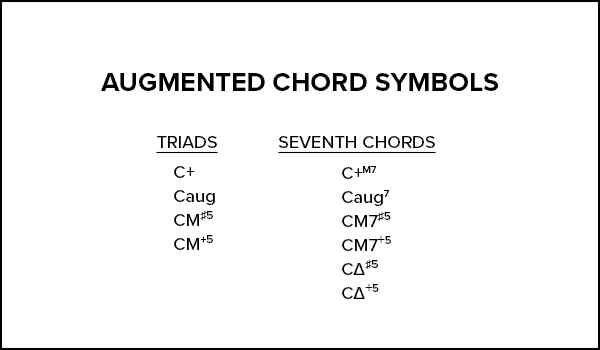

Augmented, diminished, and half-diminished chords introduce some new symbols in conjuncture with the symbols we’ve already covered. In augmented chords, the “plus” sign (+) is often used to signify raising the fifth by a half step. You may also see sharps (♯) or an abbreviation (aug.).

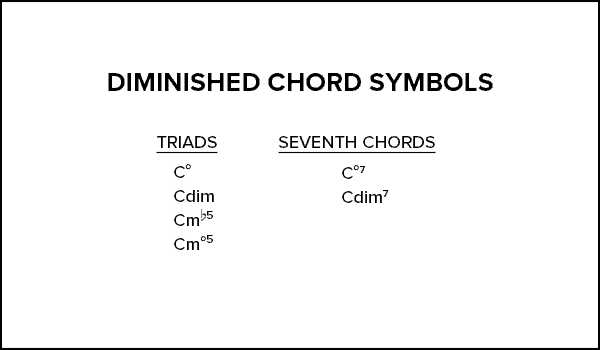

Since augmented chords use plus signs (+), it would make sense for diminished chords to use minus signs (-), right? Unfortunately, this is not the case. Remember that the minus sign (-) is used to signify minor chords. The typical symbol for a diminished chord is a small circle (o). “Cdim” is also regularly used, especially by guitarists.

The half-diminished chord symbol is very similar to the diminished chord symbol; however, you can tell the difference between the two by a diagonal slash through the small circle (ø). You will also regularly see “Cm7♭5” representing a half-diminished chord (another standard for guitar tabs).

Added Tones

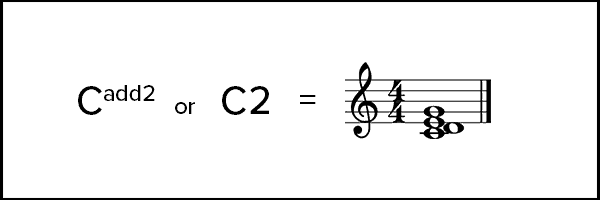

Added tones are notes added to a chord outside of the 1-3-5 (root-third-fifth) structure. The most commonly added tones are 2, 4, 6, 9, 11, and 13. Scale degrees 2, 4, and 6 imply that they are being added to a triad, while tones 9, 11, and 13 imply that they are being added to a seventh chord (since they extend past the 7th).

When tones 2, 4, or 6 are added, they will always be accompanied by one of the following symbols:

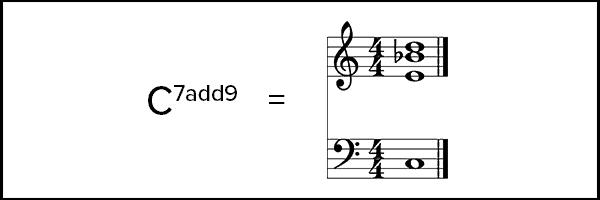

Tones 9, 11, and 13 can get confusing because they extend past the octave of a regular diatonic scale. So tone 9 is essentially tone 2 up an octave, tone 11 is tone 4, and tone 13 is tone 6. However, as we previously stated, 9, 11, and 13 imply that these tones are being added to a seventh chord. Likewise, when they are added to a chord they will be notated as:

We don’t use C9, C11, or C13 as symbols for added tones because these symbols pertain to 9th chords, 11th, chords, and 13th chords, which we will cover next.

Extended Chords

Extended chords add notes above 7th chords. Commonly found in jazz music, these chords are 9th, 11th, and 13th chords. It is not necessary (or even possible in some cases) to play every note in these chords. However, without the 7th, these chords are not extended chords but are the previously explained added tone chords. The symbols for these chords are very similar to the symbols for seventh chords:

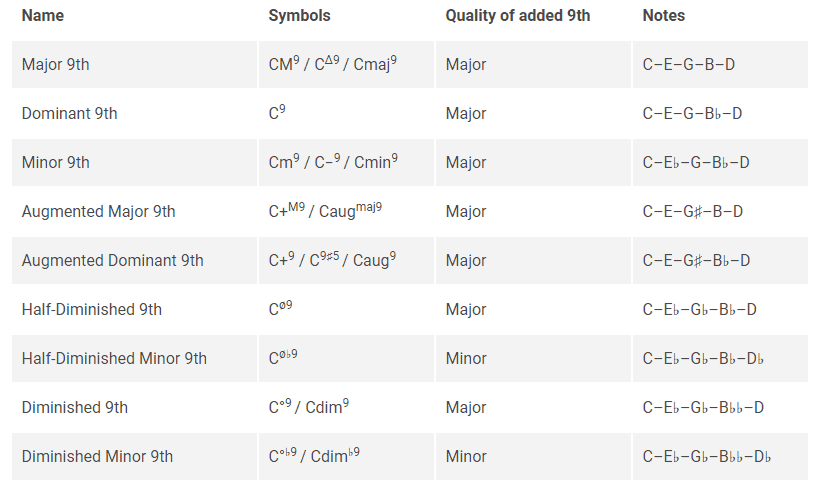

9th Chords

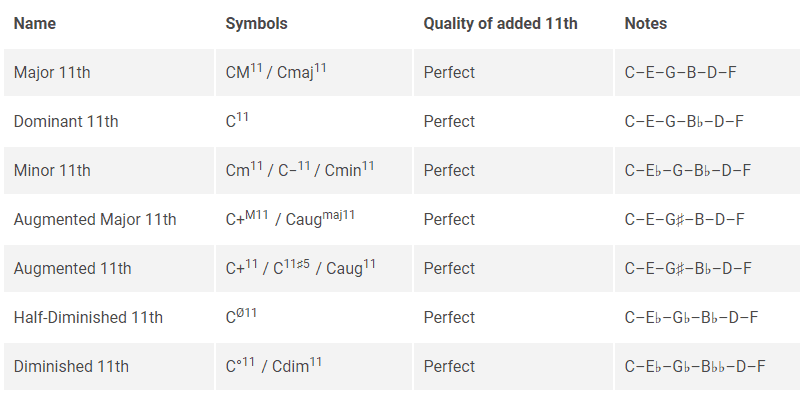

11th Chords

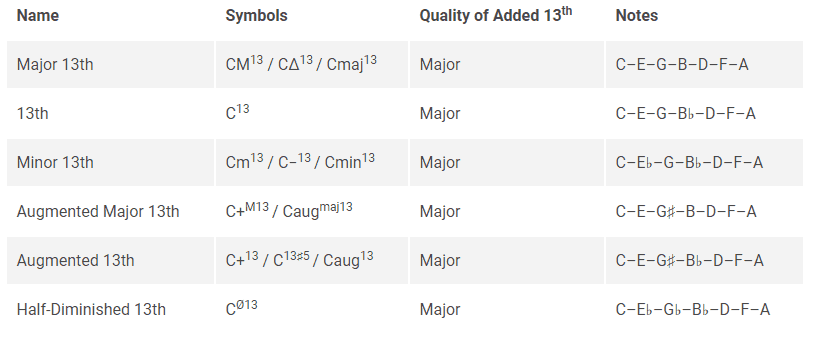

13th Chords

Suspended Chords

Suspension in music is a means of creating tension by prolonging a note while the underlying harmony changes, generally on a strong beat. There are many different ways that chords will be suspended, but when notated, you will primarily see the symbols:

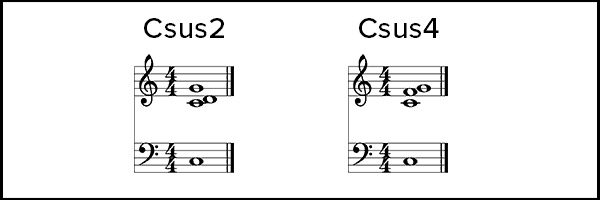

sus2 or sus4

You may also see “sus” by itself, in which the suspended 4th is implied.

If you see sus2, that means that the second scale degree should be played in the chord. For example, in Csus2, you would have a D in the chord. In the same way, sus4 means that the 4th is found in the chord (usually instead of the 3rd). So a Csus4 (or Csus) chord would have an F in it.

Inversions

Inversions are the rearrangement of notes in a triad or seventh chord so that different scale degrees are in the lowest position of the chord. Different symbols represent different inversions for both triads and seventh chords. If you’ll remember back to our first example, “Can’t Help Falling in Love” by Elvis Presley, we talked about a chord: C/B♭, which meant that a C major chord was being played over a B♭ in the bass. Inversions appear in the same way.

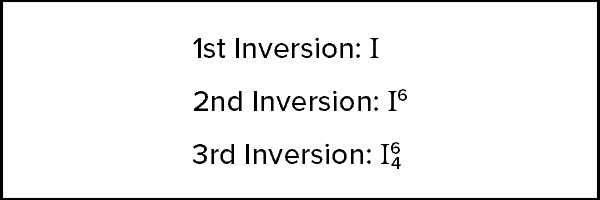

Triad Inversions

- Root Position: The Root or Scale Degree 1 is in the Bass

- 1st Inversion: The 3rd Scale Degree is in the Bass

- 2nd Inversion: The 5th Scale Degree is in the Bass

Let’s say you have a first inversion G Major chord. You will most likely see it written as G/B, which means you are playing a G major chord with a B (the 3rd scale degree) in the bass. In the rare occasion that you are using Roman numerals, you will see different symbols.

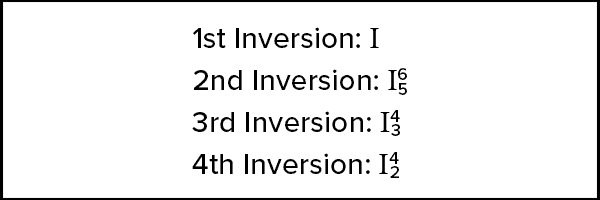

Seventh Inversions

- Root Position: The Root or Scale Degree 1 is in the Bass

- 1st Inversion: The 3rd Scale Degree is in the Bass

- 2nd Inversion: The 5th Scale Degree is in the Bass

- 3rd Inversion = The 7th Scale Degree is in the Bass

The same rules apply with seventh chords; however, your chord will now contain the seventh chord symbol. For example, if you had an Am chord in the second inversion, you would see Am7/E. There are also separate symbols for seventh chord inversions if Roman numerals are involved.

For further explanation on Roman numerals, check out our Glossary of Music Terms.

Now that we’ve unleashed an overwhelming amount of music symbols on you, you’re ready to start dissecting your music! Like any new piece of knowledge, it will take time to commit these symbols to memory, but the more music you play, the more you will see them and start becoming familiar. In no time at all, you’ll be reading these symbols like the back of your hand!