Note Beaming and Grouping in Music Theory

Not only are we going to cover how to beam notes together, but we’re going to dive into how to group those beamed notes and rhythms depending on the time signature!

In music theory, notes with less rhythmic value than a quarter note, such as an eighth or sixteenth note, have “tails” attached to them. Connecting several notes with tails is what we call “beaming.” Beaming notes together is important because it makes sheet music significantly easier to read. Not only are we going to cover how to beam notes together, but we’re going to dive into how to group those beamed notes and rhythms depending on the time signature.

If you’re feeling a little lost, check out our articles How to Read Sheet Music and A Complete Guide to Time Signatures to give yourself a refresher!

Beaming

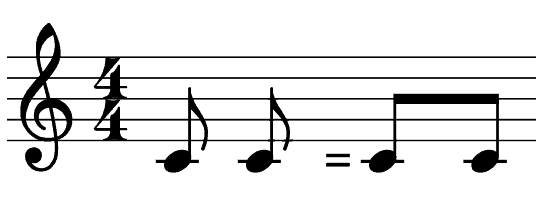

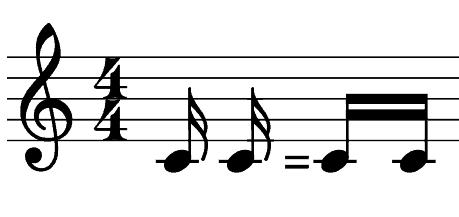

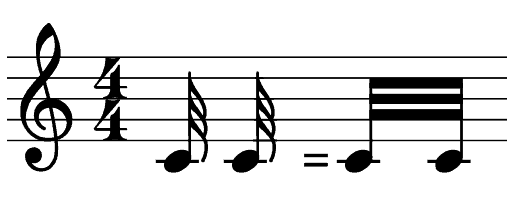

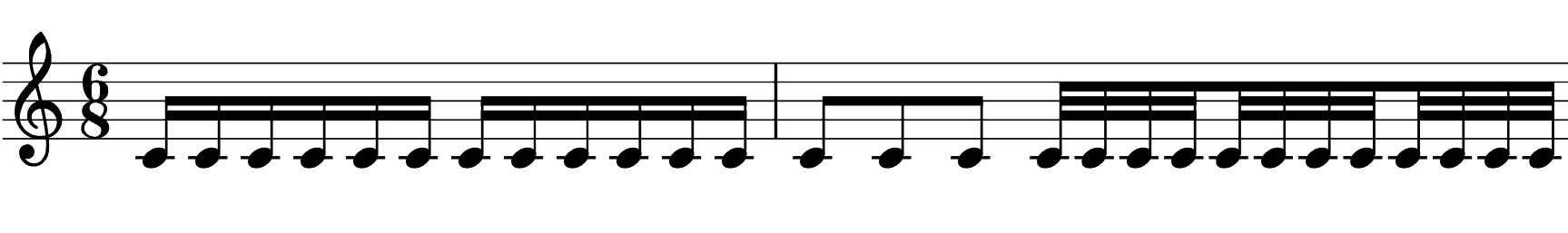

Before we get into grouping, let’s first cover how to beam together eighth notes, sixteenth notes, and thirty-second notes.

Eighth notes are connected by a single line.

Sixteenth notes are connected by two lines.

Thirty-second notes are connected by three lines.

Grouping: The Rules

More than two notes can be connected in music, but start connecting too many, and your music will get just as confusing as it would have been without any beaming. Because of this factor, there are general “grouping” rules in sheet music. These rules generally stay the same for all simple and compound time signatures:

- Do not beam across a bar line.

- All beaming takes place within the measure! If you have a stray eighth note at the end of a measure, it should be written with the tail, rather than connected to the first beat of the next measure.

- Do not beam across the center of a measure.

- For example, in 4/4 time, the center of the measure lies between beats two and three. These beats are almost always separated to ensure clear rhythm for the reader.

- Sixteenth Notes are grouped by beat.

- For example, in a meter where the quarter note gets a beat, a maximum of four sixteenth notes should be grouped together. If a dotted quarter note gets a beat, a maximum of six sixteenth notes can be grouped together.

- Thirty-Second Notes are grouped by beat.

- For example, in 4/4 time, a maximum of eight thirty-second notes can be grouped together. But because the triple lines of thirty-second note beams can get a little messy, we connect groups of four with a single line.

These rules will make more sense once we get into individual time signatures, so let’s get started!

Grouping: 4/4 Time

We’re going to start with 4/4 time since it’s the most common time signature.

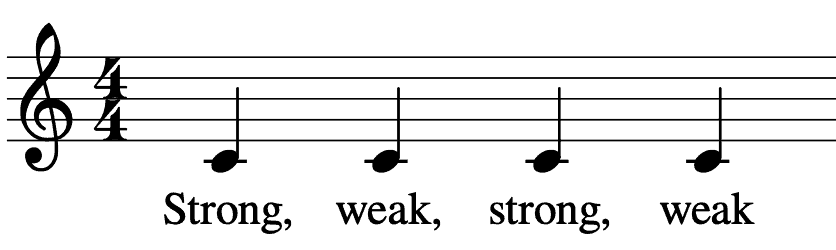

Every time signature has “strong” and “weak” beats. In 4/4 time, beat one is the strongest beat in the measure. Beats two and four are weak, while beat three is the secondary strong beat, meaning that it’s strong, but not as strong as beat one.

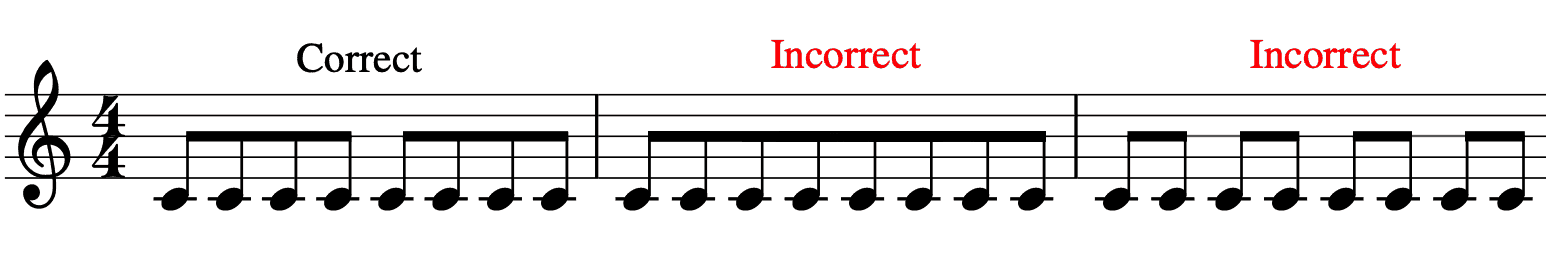

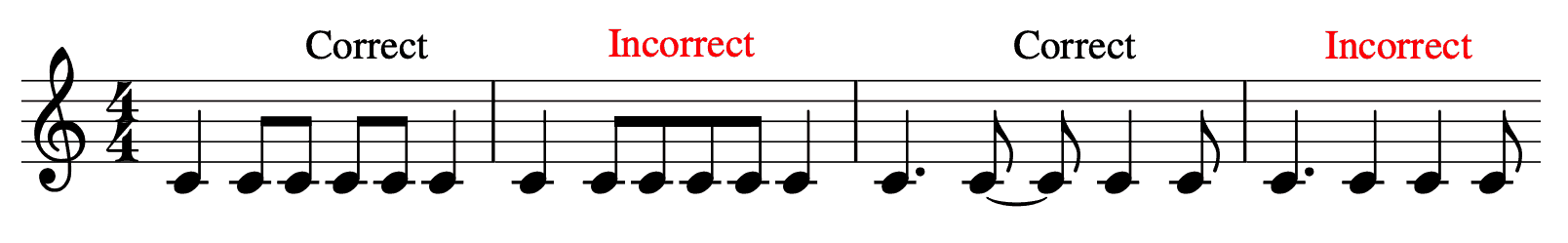

Now that you’ve seen where the “strong ” beats lie, you can see why it’s important not to beam over the middle of the measure. In 4/4 time, beats two and three should always be separated. However, beats one and two can be grouped together, as well as beats three and four. Observe how to beam eighth notes in the example below.

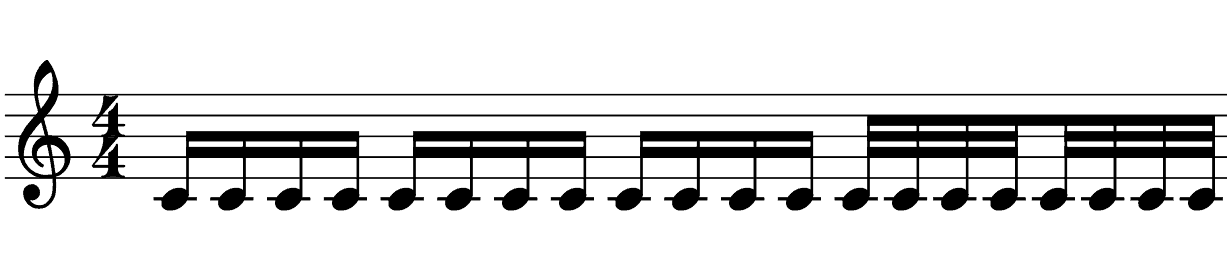

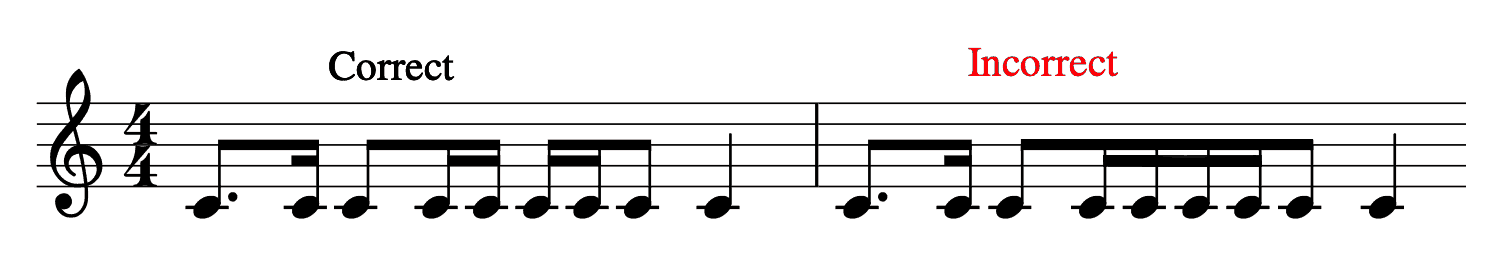

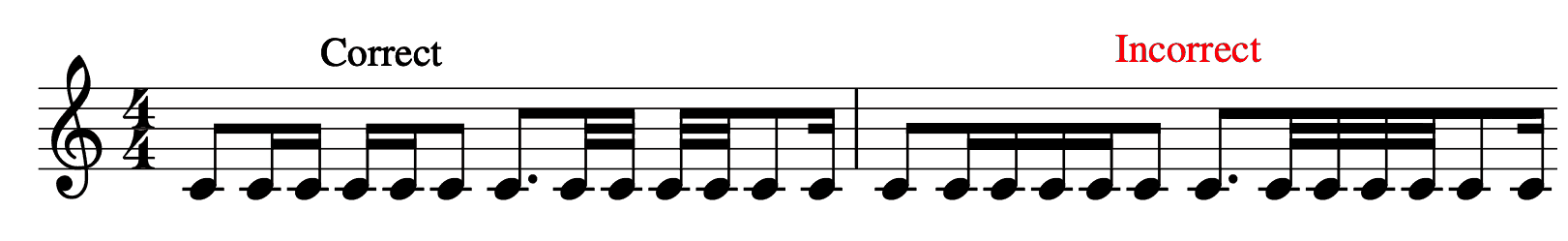

Remember that both sixteenth and thirty-second notes should be grouped by beat. In 4/4 time, this means that there will be a maximum of four sixteenth notes in a beat, and a maximum of eight thirty-second notes in a beat. Recall the single line that connects two groups of thirty-second notes.

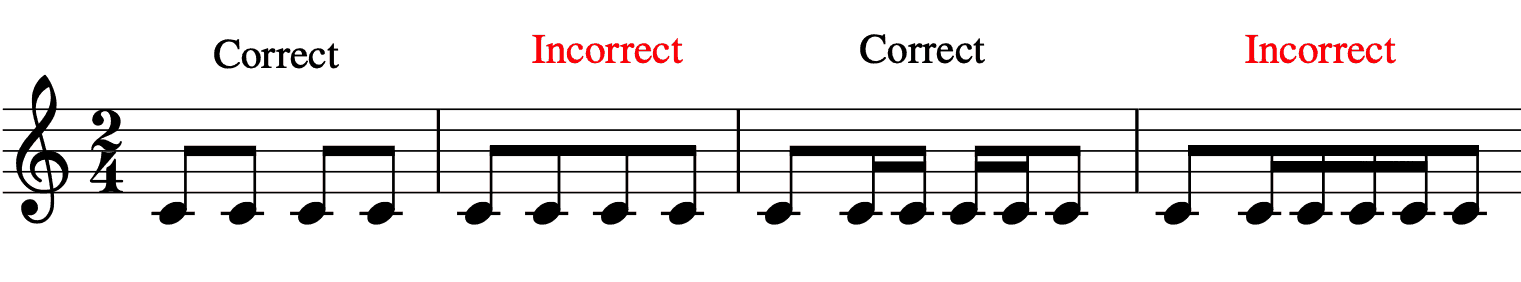

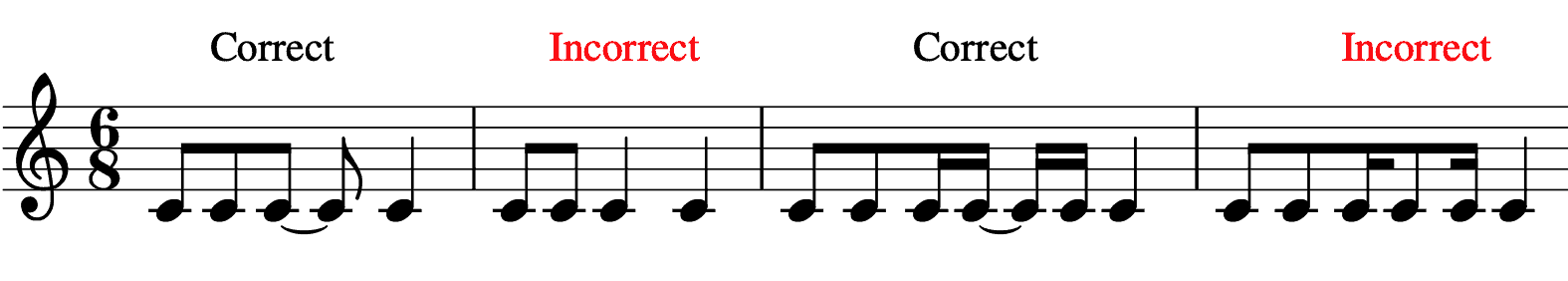

Now, let’s look at some examples of correct and incorrect beaming in 4/4 time. Remember the rules!

Are you starting to see how the correct examples are much easier to read than the incorrect examples?

Grouping: 3/4 Time

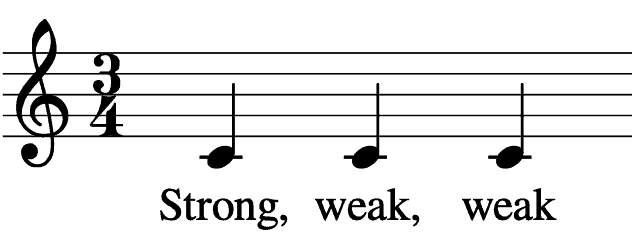

In 3/4 time, beat one is the strongest, while beats two and three are both considered weak.

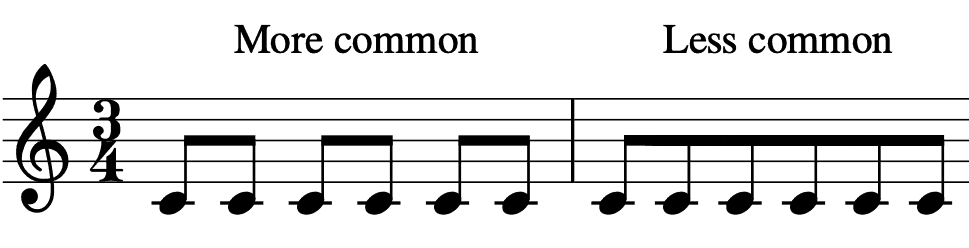

Because there is an odd number of beats per measure, the “center” of 3/4 time is in the middle of beat two. However, as both beats two and three are weak, there is no need to separate them. Though most choose to group eighth notes by beat in 3/4 time, both of the following groupings are correct:

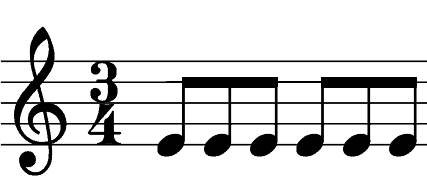

It’s important to note that eighth notes in 3/4 time should not be grouped like this:

Remember that 3/4 is a simple time signature, meaning that the beat is divisible by two, not three. This grouping is actually the correct grouping for 6/8 time, which we will come back to later.

Sixteenth and thirty-second notes are the same in 3/4 time as they are in 4/4 time since the quarter note is still the equivalent to one beat.

Grouping: 2/4 Time

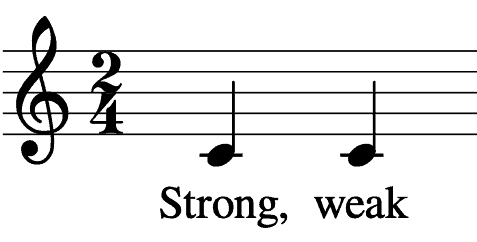

In 2/4 time, beat one is strong and beat two is weak.

The center of the measure in 2/4 time is between beats one and two, so remember: don’t beam over it! Again, the quarter note is equivalent to one beat, so we can have a maximum of four sixteenth notes per beat, and eighth thirty-second notes per beat.

Grouping: 6/8 Time

We’re moving onto a compound time signature, which means, everything changes! Yay! 6/8 will be the only compound time signature we cover, as it’s by far the most common, and once you get the hang of it, 9/8 and 12/8 will be pretty self-explanatory.

It’s important to remember that in compound time signatures, the beat is divided into three equal parts, while in simple time signatures, the beat is divided into two equal parts. Because of this, in 6/8 time, there are six eighth notes per measure, but it often feels like there are only two beats. If this isn’t ringing any bells, take a moment to review compound time signatures here.

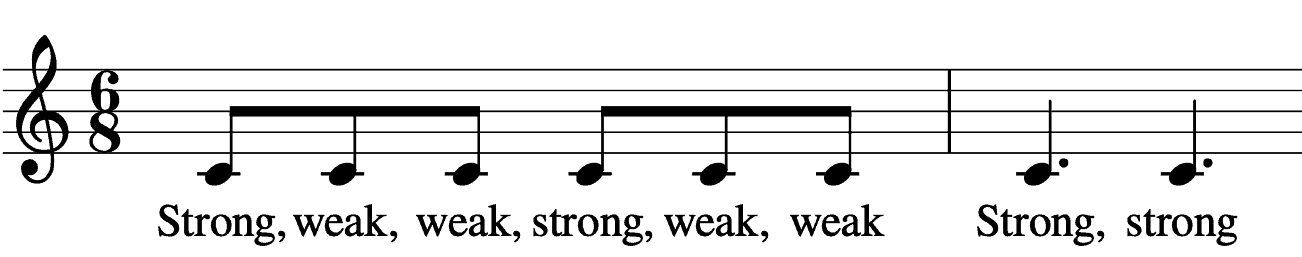

In 6/8 time, we will refer to the eighth notes as “divisions” rather than beats. Divisions one and four act as the two beats, with one being the strongest out of the two. Divisions two, three, five, and six are all weak.

The center of the measure in 6/8 time is between divisions three and four, so we keep them separated, as indicated in the image above.

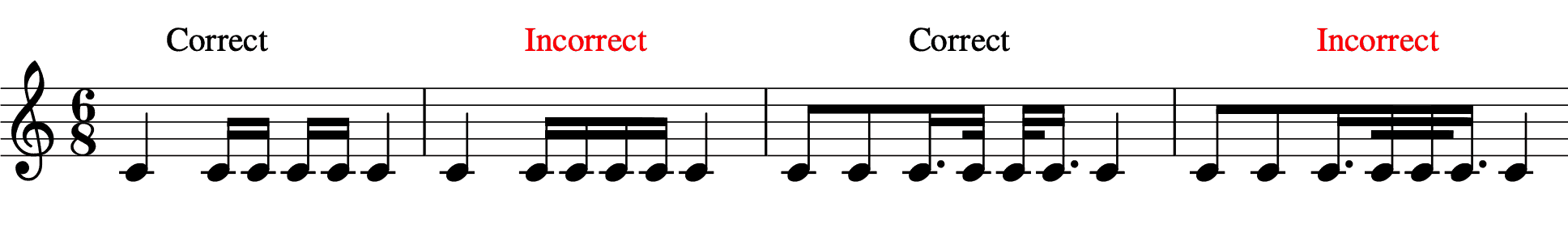

Now that we’re in compound time, the beat has changed from a quarter note to a dotted quarter note. So instead of four sixteenth notes per beat, we now get six, and instead of eight thirty-second notes per beat, we now get twelve. Thirty-second notes, however, will still be in subgroups of four, connected by a single line.

Now, let’s observe some examples of correct and incorrect groupings in 6/8 time. Remember the rules!

Now that you’ve gone through several examples, you’re probably starting to get the hang of beaming and grouping in sheet music. As we’ve mentioned a few times, the only reason there are “rules” around these things is to make reading sheet music easier, which all musicians can appreciate! We hope you’ve learned a little something today, and don’t forget to check out our other music theory posts on Musicnotes NOW for even more help.