How to Write a Song: An Introduction to Songwriting

Want to learn how to write a song? In this introductory guide, we’ll help you unpack the basics including song form, chord progression, melody, and more!

Have you ever wanted to take your love of music to the next level by writing your own? Though it can be an exciting venture, it can be challenging to get started. After all, there are a lot of components to a single song. You have to think about the structure, the chord progression, the lyrics, the message, and so much more! We’re here to teach you how to write a song and get you off on the right foot.

Determine Your Process

Spoiler: There is no one way to write a song.

Everyone’s songwriting process is a little different, and so the first step in writing a song is to think about how you are going to write it. Do you want to start with the lyrics? The melody? The chord progression? If you’re not sure, think about which component of songwriting comes to you most naturally. For example, perhaps you keep a journal and like to write on a regular basis. Try tackling the lyrics first.

Knowing how to write music and how to write lyrics are two different skill sets. Don’t get discouraged if one is easier for you than the other, especially in the beginning. You can always team up with a songwriting partner to help you get the ball rolling. Have a friend who loves to write poetry? Great! Ask them for a lyric or two.

You can experiment with your process until you find something that works for you. As you grow in your songwriting, you may even change up your routine from time to time. In any case, you have to start somewhere, so decide which component of the song you’re going to tackle first, and give it a go!

Song Form

There are several different types of song forms, and your song needs to fit into one. Without a form, your song will have no structure, and it will be hard to follow. The most common types of song forms are

- Verse/Chorus

Verse/Chorus songs usually alternate back and forth between the verse and chorus, though many times there will be a doubled verse or doubled chorus. In any case, there are only two principle melodies throughout the song. Examples include “Make You Feel My Love” by Adele and “Your Song” by Elton John.

- Verse/Chorus/Bridge

Similar to the Verse/Chorus structure, the Verse/Chorus/Bridge formula adds a contrasting section (the bridge) at the end of the song and is typically followed by a final chorus. Examples include “Fix You” by Coldplay and “A Million Dreams” from The Greatest Showman.

A note about bridges: There are really great bridges that make a song a classic and then there are forgettable bridges that we ignore while waiting for that last chorus to come in again. What’s the difference and how can you write a great one?

A successful bridge has to change something about the song, either lyrically or musically. Lyrically, it can reveal new information to us that makes us interpret the last chorus differently. Maybe you really aren’t heartbroken about the breakup, and we find out in the bridge.

Musically, the best bridges introduce some interesting chords or other musical elements. You can try a chord or two you haven’t used elsewhere in the song. Flip your chord progression around. Add a zither. If you want an exciting bridge, something has to change.

- AAA

AAA song form indicates different verses with the same melody and no major contrasting sections. It does not have a chorus or a bridge, but the melody is kept interesting enough to avoid the song sounding too repetitive. Examples include the traditional hymn, “Amazing Grace” and “Sound of Silence” by Simon & Garfunkel.

- AABA

The AABA song form is similar to the AAA form, except that it contains contrasting “B” section before the last “A” section. Examples include “Blackbird” by The Beatles and “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz.

Some songs may also contain a “Pre-Chorus” leading up to the chorus. This section is like the glue from the verse to the chorus. Examples of pre-choruses can be found in “Billie Jean” by Michael Jackson and “All of Me” by John Legend.

Keep in mind that when it comes to song form, you can take some liberties. You don’t have to follow a formula verbatim, but these forms serve as a starting place for your song’s structure.

Chord Progression

The possibilities for chord progressions in songs are endless, and that can make it difficult to get started on your own. Before you decide on your progression, you’ll need to pick a key for your song. You can then build your progression around that key, using the I chord (tonic) as your center.

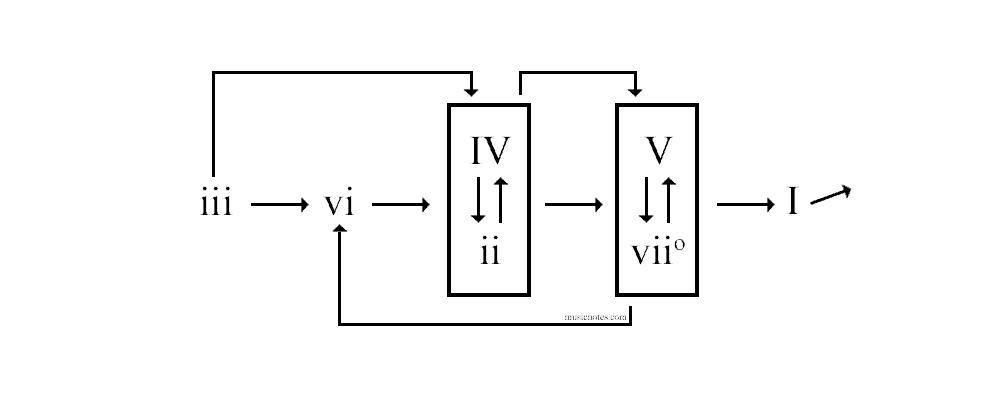

There are some general rules regarding movement from one chord to another. We’re going to look at the rules for major keys, since the majority of songs are written in these keys, and they are a good starting place for a beginning songwriter. We’ll be using Roman Numerals, so if you’re not sure what these stand for, check out our guide to Roman Numerals in sheet music here.

The I chord (tonic) can go to ANY of the other chords.

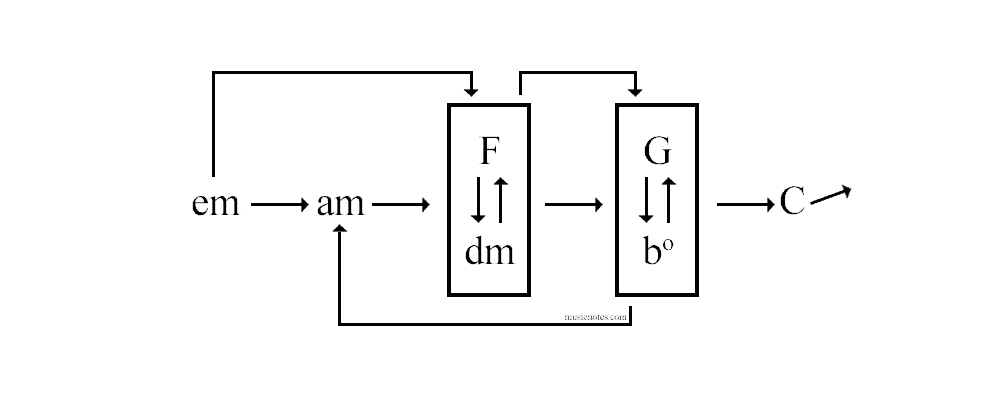

For a better understanding, let’s exchange the Roman Numerals for the chords in the key of C Major.

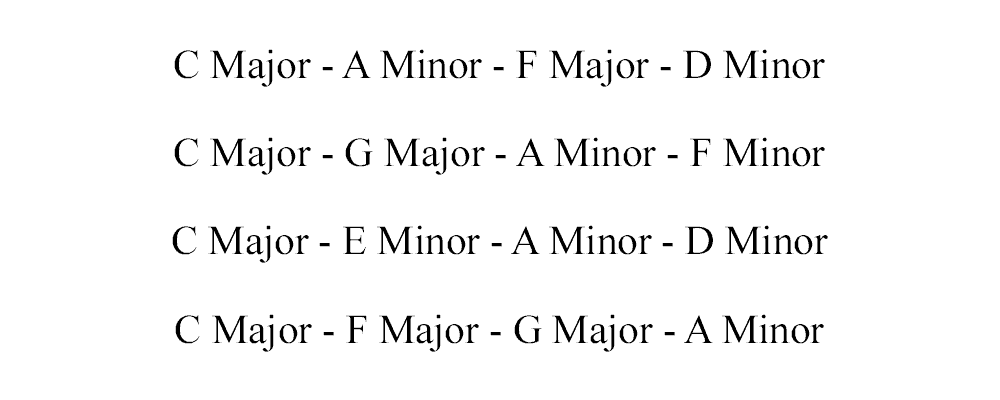

Again, you don’t have to follow this chart exactly. As your songwriting develops, you will likely experiment more with inversions, borrowed chords, secondary dominants, and more! But for a starting place, you can use this chart to get you from one chord to the next. Using this chart, here are a few examples of progressions you can use in the key of C Major.

The I-IV-V-vi progression is very common in pop music.

Other commonly used chord progressions include:

- I-V-vi-IV (sometimes called the Don’t Stop Believin’ Progression)

- I-vi-IV-V

- I-V-bVII-IV

- vi-IV-I-V

- I-IV-V

For your song writing purposes, consider these chord progressions to be jumping-off blocks. You can start messing around with them and see where they take you. You can certainly use them straight up, as they are, countless famous musicians have. You can also change them and turn them around to suit your needs.

Melody

Your melody will come naturally from your chord progression, as you will be pulling out notes from whatever key you’re in. Generally speaking, there are a few things you should keep in mind when settling on your own melody.

- Your chorus should sit higher than the verses.

The chorus is usually the heart of the song and therefore is the most dominant in the melody. Your verses should be in a lower register so that when the chorus comes in, it’s the obvious climax.

- Songs without choruses need variety.

We touched on this a bit in the song form section, but if you’re writing in the AAA song form, you’ll need a bit of movement at some point in your melody to avoid the song sounding too repetitive.

- Do you want people to sing along?

If you’re writing a song you intend for others to be able to easily learn and sing along, you will want to simplify your melody. Make it something anyone could hear and repeat back to you!

- Keep it catchy!

We all know those songs that get stuck in your head for days on end. These kinds of songs are the ultimate goal for a songwriter! A good way to test this is to try singing your song first thing in the morning, the day after you’ve completed it. Don’t listen to any recordings or look at any lyrics or music, and if you can remember it from the day before, you have a good song on your hands!

Lyrics

Song lyrics are the most common place to get stuck in the songwriting process. The first thing you need to determine before you begin to write your lyrics is the message of your song. What is it about? What do you want listeners to know–or not to know? You need to have a theme so that you can orchestrate your lyrics around that theme, instead of having a bunch of random lines that don’t go together.

Some good things to incorporate into your lyrics are…

- A rhyming scheme.

Think of lyrics as sung poetry. Rhyming schemes provide structure and are pleasing to the ear. Utilize sites like Rhymezone and Thesaurus.com to give you options when you’re stuck. To dive deeper into rhyme schemes in our article “Enhance Your Songwriting With These Rhyming Schemes.”

- Repetition.

Less can always be more in songwriting. Just look at Leonard Cohen‘s “Hallelujah.” The rich storytelling lyrics of the verses are followed by a simple repetition of the word “Hallelujah” in the chorus. So if you have a word or phrase you’d like to emphasize in your song, don’t be afraid to experiment with repetition!

- Imagery.

Songwriters are in a sense, storytellers, and it’s your job to paint a picture within your lyrics. Don’t be afraid to test out different adjectives and metaphors. Ed Sheeran demonstrates this well in the first three lines of “The A-Team.”

White lips, pale face

Breathing in snowflakes

Burnt lungs, sour taste

- Mystery.

There’s something to be said for having a bit of mystery in your songs. You want to leave your listeners thinking. If you’re too specific or you give too much away, you lose a little bit of empathy and room for interpretation. Of course, if you have a particular message you want to get across, you can be as detailed as you wish, however, you should still incorporate thought-provoking lyrics. Mystery promotes the longevity of a song. Otherwise, your listeners will get the message the first time through and not feel the need to revisit the song.

A few things to watch out for when writing lyrics are…

- Emphasis.

Rhythms and lyrics don’t always match, and you will want to be conscious of emphasizing the correct words and syllables in your lyrics. For example, if you had the word “sorry” in your song, you’d want the emphasis to fall on sorry–not sorry.

- Crowded lyrics.

Try to avoid cramming in a bunch of lyrics into a small space. If it’s hard for you to sing it, it will be even harder for your listeners to repeat it. An excellent way to avoid this is to count out how many syllables your phrase should have according to the rhythm and then match your lyrics to that number.

The Hook

The hook may be the most important component when learning how to write a song. At least, if you want to write hit songs. What’s the hook, you ask? It’s the earworm that won’t leave you alone. When you think of the band The Village People, what comes to mind? You’re probably singing “YMCA” right now. That’s the hook of that song. Other great hooks are “Stayin’ Alive,” “The Winner Takes It All,” and “To The Left, To The Left.”

The hook is frequently the title of the song, but it doesn’t have to be. It most often comes in the chorus but can show up in the bridge or a verse. In Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’” it doesn’t show up until the coda, but what a way to go out!

The hook needs to be catchy, clever, and repeatable. It should be a short phrase, not more than four or five words. It should, in its own pithy manner, sum up the emotional content of the song. To learn great hook writing, study your favorite songs. Find the hooks. What makes them memorable? How did those hooks help propel that song’s success?

Final Tips

Now that we’ve gone through the individual components of writing a song, you’re ready to give it a try. Here are a few final tips before you dive in!

- Listen to some of your favorite artists and songwriters, taking notes on the specific things they incorporate into their music.

- Free write for 5-10 minutes before tackling lyrics.

- Don’t spend too long on one word or phrase. If you feel stuck, move on, and come back to the section later. You can also check out this article: Beat Your Songwriting Block with These 5 Exercises.

- Write as often as you can. Like anything, songwriting takes practice. You will become better over time, so it’s essential to get into a routine of writing often, even if you end up scrapping a song or two.

- Turn off the inner critic for a bit. When you’ve finished your song, play it. Enjoy it. Make a video and put it out there for your friends. Don’t criticize it yet. Let it breathe for a month, then go back and ask yourself, “What could I change to make it better?” Change it on your next song.

Remember, even the greatest songwriters in the world have written songs they don’t like. So don’t give up when a song doesn’t turn out the way you want it to. Try again, and again! And soon enough, you’ll find you quite enjoy your music, and we’re sure that others will too.

FAQ

- Can you write songs if you can’t sing? Absolutely. Look at Leonard Cohen 😉

- Is song writing hard? Sometimes. And sometimes it’s easy. The important thing is to just do it.

- What makes a good songwriter? A good songwriter has something to say. They have emotions to express or a story to tell. Then they figure out the best way to get the message across through music.